Early screening for learning disabilities ‘would make a huge difference’

This story is part of the SoJo Exchange from the Solutions Journalism Network, a nonprofit organization dedicated to rigorous reporting about responses to social problems.

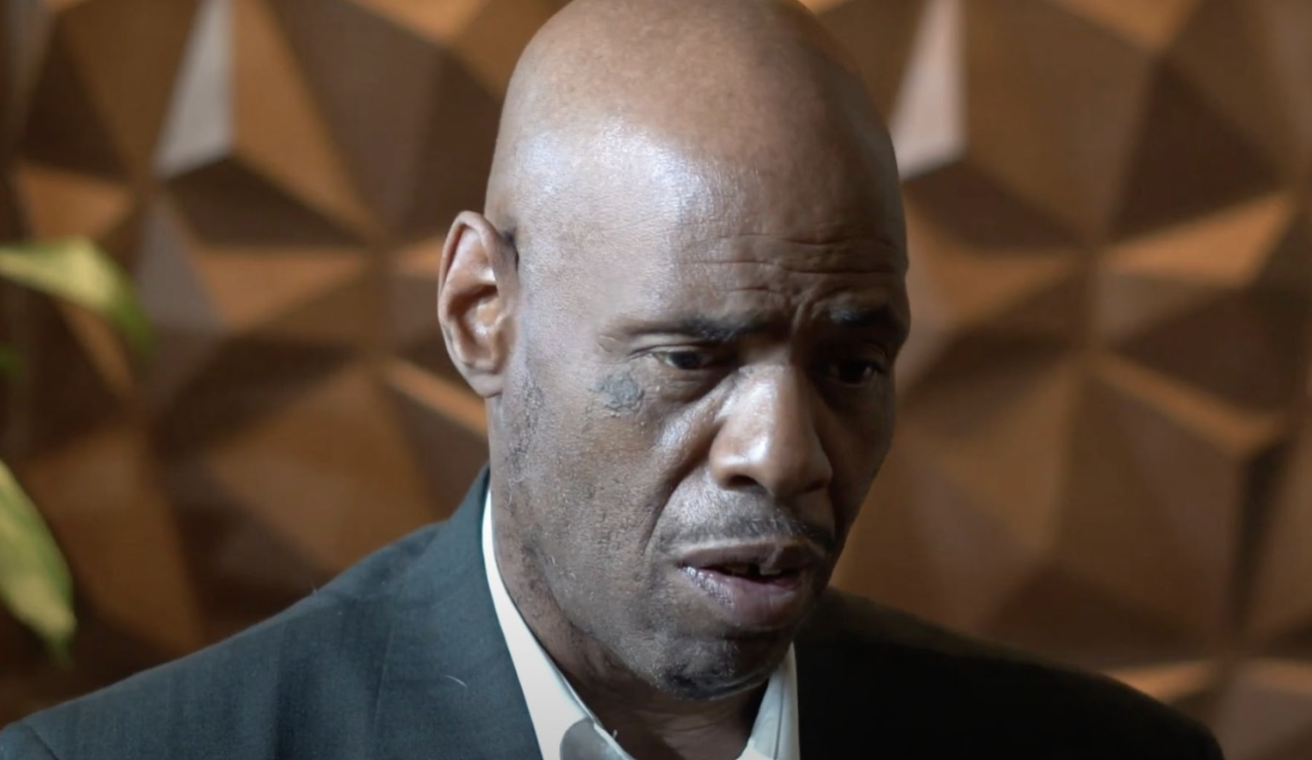

Frank Pinckney wonders what his life could have been like if his parents and teachers had believed what he now believes: that as a child he had a learning disability, attention deficit disorder (ADHD) and suffered from trauma after a sexual assault.

As it turned out, none of these problems were diagnosed, which may help explain why Pinckney’s life spiraled into crime and mental illness, and substance use disorder.

“The older I got, the more my drug habit escalated,’’ he says. The spiral ended at age 32 with a three-year prison term.

The case of Pinckney, a 62-year-old Black man who grew up in a poor neighborhood in Washington, D.C., illustrates why some experts are calling for increased early testing and screening of children for learning disabilities and differences.

“If we could do this for kids when they’re little, when they still love to learn, when they're excited to go to school, before the love of learning has been beaten out of them, it would make a huge difference,” says Teresa Giral, a clinical psychologist who heads a counseling and assessment center in the Maryland suburbs of Washington.

Instead, she says, “we wait for them to fail before we intervene.”

And Giral says the need is greatest where kids have the least. “Every child in every community should have the same access to the same kinds of things that kids have in wealthy communities,’’ she says. It’s “a civil rights issue.”

A feeling of helplessness

Pinckney says he was a hyperactive, unfocused child. However, due to the lack of a diagnosis, he was never treated.

From the beginning, he struggled in school. He had trouble reading and even comprehending the material presented by the teacher.

At 9 years old, Frank was sexually assaulted in an apartment building basement by some older boys in his neighborhood. But he said nothing to his family about the trauma; instead, he began to think secretly and constantly about revenge.

He also began to fight. He estimates that by the time the school year ended, he’d been in 15 to 20 fights – suicidal behavior, he says in retrospect.

It was bad enough that his parents and teachers didn’t understand his problems; he didn’t understand them himself. He felt helpless, which is why he says he turned early on to marijuana and alcohol when he was 9, and later to crack, PCP, and heroin.

It wasn’t until Pinckney was well into adulthood, and sought help at the McClendon Center, a Washington social service agency that treats and supports people with mental illness, that he got a diagnosis of ADHD and other mental health disorders. After getting mental health treatment through New Hope Health Services, Pinckney will soon move into transitional housing with that organization’s help.

Experts say it shouldn’t have taken that long for Pinckney to find out what was wrong. But they say he’s far from unique.

The concept of learning disabilities, along with the term itself, originated in the U.S. during the early 1960s. The symptoms of learning disabilities include difficulty reading, writing or understanding instructions, lack of concentration, poor memory, and low academic achievement. A child of the era – like Pinckney – with learning difficulties in school was often labeled as brain-damaged or a slow learner.

Kathy Essig, who worked as a special educator for over 30 years and founded the Essig Education Group to offer executive function coaching, says that when she began teaching in the ‘80s, counties would have specific disability benchmarks that would exclude many students from receiving accommodations.

For many parents, Essig says, turning towards private screenings and private schooling was the solution because it was much easier to get accommodations at private schools. But this would leave out children from low-income families, like Pinckney, whose parents could not afford private schooling.

Screening for learning disabilities has improved significantly since then. Children should receive behavioral and developmental screenings at 9 months, 18 months, and 30 months, according to The American Academy of Pediatrics.

But not all children even see a pediatrician during these milestone ages, for reasons ranging from lack of transportation to a caregiver’s work schedule to – most recently – the pandemic. Some pediatric offices also lack the time or staff for the recommended screenings, and federally funded developmental programs that offer such screenings, such as Early Head Start (for kids from birth up to 3 years) and Head Start (children 3 and older), regularly have long wait lists.

Studies show that many of the nation’s two million children or young teens with a learning disability — which include dyslexia, and other language or number-processing disorders — are diagnosed only in second or third grade, after they’ve fallen behind their classmates. Without screening or testing, even alert teachers or other school staff often don’t spot the need. Many children are never diagnosed or treated at all, especially, according to experts, low-income children of color.

The majority of students enrolled in Title I schools, at least 40% of whom come from low-income families, are Black and Hispanic students. These schools often lack funds for screening and early intervention.

Giral is working on a study of undiagnosed learning differences, including dyslexia and ADHD, among fifth graders with varying socioeconomic backgrounds in three elementary schools in Maryland, Washington, D.C. and Louisiana.

In a Title I public school in Louisiana, where 95% of students are eligible for free or reduced-cost lunch programs, Giral’s preliminary, unpublished results show that almost 90% of tested students — none of whom were in the school’s existing accommodations program — showed signs of attention and focus issues when administered a commonly used computer test.

That compares to about 50% at Catholic schools in Washington’s affluent Georgetown neighborhood and in a middle-class neighborhood in Maryland. Public schools in the district and two counties in Maryland and Northern Virginia declined invitations to participate in the study, Giral says.

The test, which is often used to detect ADHD, measures a child’s executive function abilities, including the ability to maintain attention and ignore distractions, read and follow directions. A failure of the test, though, does not necessarily mean a child has ADHD – studies have shown that scoring poorly can also be a result of learning problems caused by other factors, including exposure to trauma, lead poisoning, and even chronic pain.

If a child can’t understand the instructions for the test due to a reading problem such as dyslexia or due to low IQ, they may also perform poorly, Giral says, making the problem bigger than just executive function issues.

Failing to recognize attention and executive function issues at an early age has significant repercussions, she says. Students who aren’t identified and given assistance may stay in a regular classroom, unable to read or sit still. “No one has tried to do anything to help them,” she says.

Giral hopes shining a light on the lack of testing will spur government action to broaden early childhood screening legislation to include testing for executive function and exposure to trauma. This, she says, would help more children feel competent in school settings. Giral and her research colleague, Louisiana-based child psychologist Lisa Tropez-Arceneaux, are reporting their findings to the participating schools this fall and hope to publish the study by year’s end.

Learning disabilities and crime

Approximately 60% of adults who struggle to read and write have either undetected or untreated learning disabilities, according to the Learning Disabilities Association of America. Many grow up without realizing the educational system has failed them and believe they simply can’t learn. Pinckney was one of them.

Trauma, such as that suffered by Pinckney in his youth, also often goes undetected. Tropez-Arceneaux says that trauma can often be overlooked because it can look like the more easily diagnosed and treated ADHD.

“How can a child sit still and attend to a teacher if they’re thinking about what has happened to them?’’ she asks.

Children living in poor neighborhoods are more likely to suffer from trauma, such as witnessing violence, living in abusive households, or experiencing physical and emotional stress from food and housing insecurity, research shows.

Pinckney remembers how his mother struggled to put food on their table, and that he, his mother and his siblings all experienced domestic violence at the hands of his father. He was about 8 years old when he began feeling deep resentment toward his family for punishing his hyperactivity and other signs of his undiagnosed ADHD.

Living with undetected childhood disabilities can have serious and lifelong implications, as Pinckney’s experience shows. Experts estimate that between 30% to 60% of detained or incarcerated youth have a disability, most often a learning disability.

Giral, who runs Bethesda Chevy Chase Counseling and Assessment, worked for a year in the mid-2000s in the D.C. Superior Court Child Guidance Branch doing court-ordered psychoeducational assessments and treatment for young people in the juvenile justice system. The experience confirmed many have undetected cognitive challenges.

“If that was caught when they were younger, they might have had a better chance at a different outcome,’’ she says, pointing out how most of the families of incarcerated youth she worked with could not afford expensive psychological evaluations on their own. These young people, she says, would get their diagnosis “finally too late” as they were about to be taken to jail.

“I really believe that if we were to assess at the earliest possible moment for all children…criminality itself would decrease.’’

Many studies have confirmed the connection between learning differences, mental health issues and criminal involvement, she says.

A story to tell

Frank Pinckney has come to realize that he wasn’t unique in his childhood struggles. As a result, he feels connected to others suffering from the same problems and wants to stand up for them.

He supports increased early childhood testing and screening for problems like his, no matter a person’s race or economic status.

He was failed by the system when he was too young to understand what was happening to him, but now he says he gets it: “I ran around for 40-something years doing drugs, the whole time, running from myself.’’

Not anymore, Pinckney says. He’s stayed off drugs for about five years, even while losing a son to gun violence and having another son shot over the course of the last two years.

He’s learned a lot from his own story, he says, including how sharing it with others can help them. He knows that using drugs will only hurt him and his family and make it harder for him to help other people who are suffering.

“What’s the purpose of getting high?” asks Pinckney. “Smoking someone else’s crack is not going to work for me anymore.”

Read More Coverage Below