The Episcopal Diocese of Maryland Is Interested In Paying Reparations To Descendants of Black Enslaved Marylanders.

How will this historic institution make amends?

The Claggett Center in Frederick, Maryland. Photo by Gary Allman (Flickr).

Photo: The Claggett Center in Frederick, Maryland. Photo by Gary Allman (Flickr).

The wind blew as the Rev. Eugene Sutton, the first Black Bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Maryland, and the Rev. Waymon Wright, former vestry at All Saints Episcopal Church in Frederick, Maryland, and activist, walked onto the Hasselbach farm, once a plantation where enslaved Black people labored. It was 2019, and they were at the former plantation to remember, as they said, the Black people who were enslaved by the Hasselbach family, a wealthy European family who had settled in Maryland. The men stood before a stone grave marker that is mounted with a bronze-colored square-shaped plaque. The plaque reads: “The Gravesite of An Unknown Enslaved Man of African Descent.”

They prayed.

At one point, still standing in front of the grave, Waymon told Sutton, who held a golden staff, that the Hasselbach family “had the area bricked-in, in order to preserve the graves of the enslaved [Black people].”

“It’s probable that other enslaved people lay here too, but few details of their lives remain,” said Sutton to Waymon in the YouTube video.

The 19th-century plantation is on the same grounds as the Claggett Center, a retreat center for the Maryland diocese and youth camp destination in Frederick County, Maryland. The center is named after Thomas Claggett, the first bishop of the Episcopal Church and one of many Episcopalians who enslaved Black people in Maryland. The Piscataway and the Massawomeck indigenous people once lived on the land. Through colonization, disease, and other factors, the indigenous people were forced from the land and resettled in other parts of Maryland or migrated north. In 1811, John Hasselbach purchased the land. Due to Hasselbach’s will, enslaved Black people over 30 years old were released from bondage. However, other enslaved men and women who were not over the age of 30 had to wait to be freed.

Eventually, the diocese purchased the property in the 1950s. In the 1970s, while digging, archaeologists discovered bones. After examination, they concluded that the bones were of a Black male. Scientists placed the bones back into the ground. Then the church placed a stone over the grave to mark the spot.

“They worked this land as they had on so many farms and plantations throughout the South,” Sutton said to Wright. “They worked it for no pay. When they worked here, no one remembered them. We in this diocese…we want to remember them.”

They talked about the diocese’s participation in the Maryland slave trade — by extension — the maintenance of white supremacy, and segregation. In the video, Sutton repented of the diocese’s sins and talked about how the church is trying to atone for its sin through reparations for Black people in Maryland.

In May 2019, delegates to the diocese’s 235th annual convention unanimously passed a resolution to engage in a study of reparations. Also in 2019, at a Congressional Hearing on H.R.40, a bill that would grant Congress the ability to study reparations and to develop proposals, Sutton testified, almost boasting, that three majority-White districts voted to pass the resolution for the study of reparations in the Maryland diocese. The study of reparations is still in its early stages, and the diocese has not made any official plans on how they would pay reparations to black people in America. Starting in April, the diocese will hold a workshop on reparations for its local parishes.

“Reparations, at its base, means to repair that which has been broken,” Sutton wrote in a June post on the diocese’s website, which reflected on the church’s engagement with the topic, and alluded to his hopes moving forward. “It is not just about monetary compensation. An act of reparation is the attempt to make whole again, and/or to restore; to offer atonement; to make amends; to reconcile for a wrong or injury.”

“For us ‘repairing the breach’ is not a mandate from a government or leader, but a mandate from our God to commit to the rebuilding of a relationship between the world and God…,” Sutton wrote in a May 2019 pastoral letter.

For this particular story, I reached out to other parish rectors (Black and White), congregants in Baltimore and western and southern Maryland (majority-White counties) to talk to them about their ideas on reparations. Most rectors did not return my emails or phone calls. The Rev. Grey Maggiano, the rector at Memorial Episcopal Church in West Baltimore and co-chair of the Dioceses of Maryland’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, was the only one to grant me a phone interview. However, some congregants did respond. White congregants said they weren’t knowledgeable enough about the subject and were still learning. They encouraged me to reach out to their pastors.

The diocese developed The Truth and Reconciliation Commission as a way to help the institution continue to research its participation in slavery and to eradicate racism within the diocese. Grey said the impact of slavery and segregation has resulted in segregated Black and white churches within the diocese as well as damage the diocese’s relationship with Black people and the Black community at large.

Maggiano said the church can’t change how it participated in the evils of slavery and segregation. But it does want to continue to have an institutional conversation about the church’s role in slavery, and by extension white supremacy and segregation. He said moving forward, they want to continue to answer two questions: What did our institution do that harmed people of color during the Maryland Slave Trade? What can the diocese now do to repair relationships with the Black community?

“It’s good to have a process of atoning, where we can go through a real spiritual transformation of ourselves; our souls; and bodies to put us on a better path,” said Maggiano.

For a year or so, I reached out to the diocese requesting an interview with Sutton. The diocese never granted me an interview with Sutton, but did encourage me via email to look at Sutton’s pastoral letters, and at the work done through the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. It should be noted that the diocese will have multiple workshops on reparations for parish members in the coming months. Also, recently, the executive council of the Episcopal Church gave out grants to its parishes to aid with the work of ethnic conciliation and anti-racism work. ( see resolution here)

However, in the June 17th blog post quoted above, Sutton may have left some clues regarding the diocese’s approach to reparations. Sutton suggested that parishes create community programs as a form of reparation. As an example, Sutton suggested the Sutton Scholars, a mentorship and academic program that began in 2016 and reaches 30 Baltimore city high school students each year. These students gather at Morgan State University, a Historical Black College or University, in Baltimore that partners with the diocese to do the program.

“When I was a youngster growing up in Washington, D.C., there were some adults who took the time and interest to help me learn things they don’t teach in school. It made a profound effect on me and prepared me for where I am today. That’s what this program is about,” said Bishop Sutton to the Baltimore Times in 2017.

His other examples, to name some, included housing programs, programs that would bring more affordable grocery stores to food deserts within the city and rural areas, and job training programs. Such programs would target Black people.

But what makes these programs reparations? I asked Grey this question via email. Unfortunately, he did not reply.

Black Bodies And Money

Slave traders came to Maryland, more than other states, to buy [enslaved Black people],” wrote Maya Davis, a research archivist at Maryland State Archives.

Anglicans and Episcopalians in Virginia and Maryland participated in two forms of slavery: plantation and institutional. Black people were brought to Virginia in 1619. The first slaves appeared on the shores of Maryland between 1634–42. However, between 1700 and 1776, the year America declared its independence, there were 100,000 Black people trafficked to Maryland and Virginia, two major slave ports in the colonies.

“Slave traders came to Maryland, more than other states, to buy [enslaved Black people],” wrote Maya Davis, senior research archivist with Legacy of Slavery Archives and legislative liaison at Maryland State Archives, in a document about Middleham and St. Peters church connection to slavery in southern Maryland.

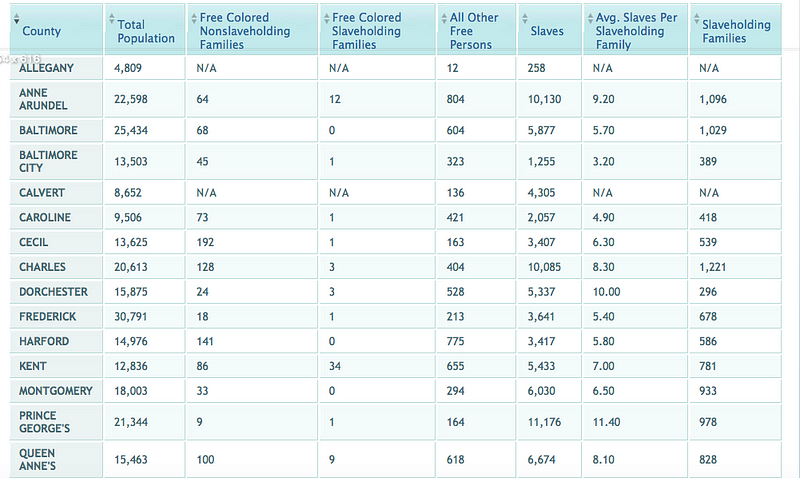

(Screenshot: The number of enslaved and free Blacks in Maryland in 1790. This screenshot is from the Maryland Archives Legacy of Slavery).

Jennifer Oast, a history professor at Bloomsburg University in Pennsylvania, wrote about the Anglican and Episcopal institutional slavery in her book, “Institutional Slavery: Slaveholding Churches, Schools, Colleges, and Businesses in Virginia.”

Though her book focuses exclusively on Virginia, this kind of slavery also occurred in Maryland as well. The Episcopal Church used glebes, portions of land owned by the church. These lands were reserved for the parish ministers, something like parsonages. The Anglican Church wanted more ministers from Europe to be theologically trained and placed at Virginian parishes, and possibly Maryland.

“They tried to make the glebe properties more financially attractive by purchasing [Black people] and attaching them to glebes…,” said Oast in a phone interview. “When the ministers took over, they would not only have land but a certain number of enslaved people who would have to farm the land as well as perform other tasks. That is the first example of institutional slavery in Virginia.”

“The ministers would get all the benefits of the glebes, but he didn’t get to pass it on to his heirs,” said Oast, who wrote her dissertation on slavery at the College of William and Mary. “When he dies, retires or leaves it, it goes to the next minister for his use and his family.” In other words, enslaved Black people were passed on from one European family to another.

Additionally, White Episcopal enslavers donated enslaved Black people to parishes for its use as well as to universities, like The College of William and Mary and Virginia Theological Seminary. Oast said enslaved Black people also worked in the parish poor houses. They did the work of caring for white poor Christians. They also worked on college campuses, many of which were started by Christian denominations for theological education, including enslaved Black people.

“[On college campuses you see enslaved Africans] do all the work that you see support staff doing today: cleaning, cooking, keeping the fire burning,” she said. “In the case of The College of William and Mary, started by an Episcopal reverend, enslaved Africans were [sold] to raise money for scholarships for poor white students to attend.”

But not only did the Episcopal Church participate in slavery; it also practiced segregation.

Dr. Lawrence Brown, former associate professor at Morgan State University, the School of Community Health and Policy, said he found evidence showing that three Episcopal Churches in Baltimore lobbied the mayor to keep Black people out of neighborhoods. Brown said these white pastors feared Black people moving into their neighborhoods. They thought, Brown explained, that the presence of Black people would hinder the church’s work for the Lord, and decrease the church’s property value.

Trying To Make It Right

This is not the Episcopal Church’s first attempt at trying to heal its relationship with the Black community. In 1967, during the civil rights movement, the Klu Klux Klan’s murderous rampage and a year before the assassination of Martin Luther King, in cities and towns across the U.S., Black people were making their voices and frustrations heard via protests. Some Black and White Episcopalians had protested with King and other civil rights clergy and non-clergy. In response, author and minister, Rev. Nathan Wright — a Black man, who was the director of urban work in the diocese of Newark, New Jersey — decided to organize a meeting in New York, diocesan headquarters, on the concept of Black Power. During that meeting, he called on white business owners to invest in Black neighborhoods. This funding was given to help Black Americans improve their neighborhoods and economic situation.

Bishop John Hines, the 22nd presiding Bishop of the Episcopal Church, wanted the Episcopal denomination to engage more with the Black freedom struggles. He believed the church could bring healing to America’s ethnic divide. But Hines didn’t understand the Black people’s struggle. So he asked Leon Modeste, a black man who eventually became director of The General Convention Special Program, to walk with him through Black communities in Brooklyn, New York. They did so. In the journal of Anglican and Episcopal History, Gardiner Shattuck Jr. wrote that that experience encouraged Hines to reflect deeper on the connection between suffering and the Christian message.

“He believed that the [Black people] he met in the ghetto had a far better sense of the reality of God than those, like himself, who had been raised in relatively privileged environments,” wrote Shattuck.

Hines organized two meetings with Black people, who were for the most part not affiliated with the Episcopal Church. He wanted to hear their ideas on how the church could work with the Black community. He wanted to share their ideas at the General Convention. William Booth, human rights commissioner in New York, who also worked with the NAACP, led the meetings. According to Shattuck, both groups responded with a report that criticized White people and offered recommendations on what the church should do. It reads:

Programs developed by White people to help Black people have failed.

The Episcopal Church needed to reform and purge the racism that infected its members.

Black Power had to be supported by committing substantial money without strings to Black people and to provide funds for economic development in cities.

However, Hines’ model of engagement with the Black community was one of pragmaticism. He ignored the recommendations to address institutional racism — and decided to just fund initiatives that could help the Black community. He convinced the Episcopal Church to set aside millions of dollars to give to Black non-Episcopalian institutions for the General Convention Special Program (GCSP). This program was the benevolent arm of the church that provided grant money to Black organizations, and one Mexican American organization, in cities and rural areas. Over the years, according to Shattuck, the church gave a little under $1.7 million in grant money.

“One of the basic goals of the General Convention Special Program has to do with the whole concept of self-determination. [An] individual, a group or a community must of their own [will] devise whatever solution they feel they have regarding their plight — and to have the control, and the power to implement…solutions…,” Modeste said in 1968 on Viewpoint, a radio program. “This is not a giveaway. Unfortunately, so many people have said that the Episcopal Church is giving money away. We are not. There is an intensive screening process that takes place.”

In 1969, James Forman - an activist, a member of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee and journalist, while at the National Black Economic Development Conference (NBEDC), an event sponsored by the Episcopal Church as well as others - encouraged attendees to draft a document. It would later be known as the “Black Manifesto.” In it he demanded reparations from white Christians and Jewish the community. Forman outlined in the manifesto, a 2,500-word document, that the money would be used to create institutions for the betterment of the Black community. On May 4, 1969, exactly a year after the assassination of King, Forman disrupted a Sunday gathering at Riverside Church in New York, sharing the demands of the Black Manifesto to a mostly white crowd.

“We are…demanding of white Christian churches and Jewish synagogues which are part and parcel of the system of capitalism, that they begin to pay reparations to Black people in this country,” wrote Forman in the manifesto.

Bishop Hines met with Forman and desired to give money to the NBEDC, but decided against it. In that same year, the Episcopal Church held its General Convention in South Bend, Indiana. The tension was high. The separation between the Black and White clergy had grown. Some White clergy members thought the Episcopal Church was moving away from its mission — evangelism. On one occasion, during the second day of the conference, a Baptist preacher, according to Shattuck, wrestled the mic from Hines’ hand as he was speaking. He demanded that the Episcopal Church respond to the Black Manifesto. There was a debate about reparations at the convention. The church rejected the manifesto but passed a resolution allowing the GCSP to fund Black initiatives.

Black clergy at the conference were incensed at this decision. Members of the Union of Black Clergy and Laity, who had criticized the denomination for being racists in 1968, felt betrayed by the move to make the GCSP the primary way to fund black initiatives. They felt that the Episcopal Church favored the GCSP because it was created by a mostly white organization and disregarded the National Convention of Black Churchmen, an organization created by Black clergy from various denominations. NCBC had started the work of black empowerment before the creation of the GCSP. The members of that organization felt overlooked.

“…Many [Black people] were outraged by the failure of White Episcopalians to recognize the work they had done,” wrote Shattuck.

Due to some White clergy’s ongoing concerns about the GCSP, the program was eliminated and somewhat repurposed to focus on Black Episcopalians. Black Episcopalians suggested that the church focus on issues that affected them. Franklin Turner, a former employer of the GCPS, was appointed to the church affairs position, which was also known as the black desk. In 1974, Bishop Hines prematurely retired from his position.

“As the momentum behind the [General Convention] Special Program trailed off, so did the Episcopal Church’s involvement in the reparations’ discussion,” wrote Mark Duffy, director of The Episcopal Church Archives, in an email. “It was not a prominent issue again until the 2000s.”

In 2006, at the General Convention, Episcopal clergy passed resolution A123. The resolution acknowledged the church’s complicity in slavery. It admitted that its participation in transatlantic slavery was sinful, and that it had betrayed humanity. The resolution also encouraged the Episcopal Church to search for ways to “repair the breach” with the Black community. It also encouraged every diocese to research how they participated in the enslavement of Black people.

Things started to happen. In 2007, Mary Klein, archivist at the Diocese of Maryland, and Kingly Smith published “Racism in the Anglican and Episcopal Church of Maryland,” a document retelling the diocese’s connection to slavery. The next year, 2008, Bishop Katharine Jefferts Schori, lay leaders, rectors, and other denominational leaders (Presbyterians, Unitarian Universalists, Baptists, Catholics, and Methodists) met at The African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas in Philadelphia. The Rev. Absalom Jones, the first Black priest, and abolitionist, founded St. Thomas in 1792. They gathered for a “Day of Repentance.” It was a time for the church to repent for its participation in the Transatlantic Slave Trade.

“We have turned away from loving our neighbors as ourselves,” said Bishop Schori in her homily. “We have degraded those who are like us under the skin so that we might use them worse than beasts of burden. We have sought to be god, lording it over others. In the process, we have repudiated that divine image in ourselves and discovered that there is little or no health in us.”

“This is a great start to a new beginning,” said Bonnie Andersen, former president of the House of Deputies.

Sutton was present on that day. He called it an “emotional day.”

“It’s part of a year of turning the clock forward in Maryland and continuing the work of fighting intolerance,” Sutton said.

On Nov. 1, 2014, marking the 150th anniversary of the end of chattel slavery in the state of Maryland, the Maryland diocese organized “A Day of Repentance and Reconciliation.” On that day, and again in 2017, Bishop Sutton and Episcopal clergy visited several churches throughout Maryland, holding services of contrition. They also retold the stories of the church’s participation in slavery and remembered those black bodies that lay in church cemeteries, some buried alongside their enslavers. Plaques, similar to one at the Claggett Center, were placed at some parish cemeteries to mark the graves of enslaved Black people, a form of symbolic reparations. Both events became a part of the Trail of Souls project, a public online archive of each parish’s connection to the Maryland slave trade.

“The wealth of Calvert County is built on the backs of slaves,” said the Rev. Ken Phelps, while at a commemoration ceremony known as Lower Marlboro Freedom Day, an annual October celebration held in Calvert County to remember the enslaved Blacks who escaped during the War of 1812. “Slavery was the engine that drove the capital enterprise. There was no mistaking that. The more interesting question, I think, is how do we respond to that?”

Reparative Acts and Reparations

Despite the diocese still trying to decide their approach to reparations, before the passing of the resolution to study reparations in 2019, Phelps had begun thinking about reparations for black people. Phelps is the rector of All Saints Church in Calvert County. I had a chance to interview Phelps, a white man, while working on another story around this same topic in 2018. He said he thought about starting a nonprofit organization, Forgotten Children of the Chains, for Black children in the county. The foundation would have an annual symposium that would discuss racism in Calvert County, and it would give scholarships to Black children who are descendants of enslaved Africans.

“Is this reparation?” he asked me. “I don’t know.”

Photo: Memorial Episcopal Church in Bolton, Hill. Photograph by Eli Pousson ( Flickr)

Rev. Maggiano said his parish, Memorial Episcopal Church, has begun grappling with how its church participated in segregating Baltimore. Memorial Church is located in Bolton Hill, a historic neighborhood in West Baltimore. West Baltimore, according to the latest demographics, is 83 percent Black. Historically, German Jews and other non-Jewish Europeans lived in the neighborhood. Wealthy White Bolton Hill residents often hired Black people as live-in servants. Also, Black people lived in what was known as alley houses. Later, as more Black people moved into Bolton Hill, white people migrated out. In the 1950s, Memorial Church operated a youth center that denied Black youth from attending.

In an attempt to right this wrong, Memorial Church members have supported enrichment programs for the children in the West Baltimore community. Maggiano refers to this as a reparative act.

“[This is] a way for us to work back against this, frankly, terrible thing that was done in our name in the past,” said Maggiano. “This is what reconciliation looks like to us — proactive action to undo the evil done on behalf of the church in the past,” he said.

Though this parish is engaged in such acts, and perhaps others, to rebuild trust, there are still unnamed persons, according to Maggiano, who want to see the diocese do more. “There is interest among some parties [within the Maryland diocese] that there be specific resolutions about the diocese transferring portions of its endowment or selling properties and using that as a reparations package,” Maggiano said.

“What we hope to do over the next year is to have more conversations about what that would look like…going forward, and who the money would go to,” he said. “I cannot speak for the whole diocese or on behalf of the bishop. I will say this. Previous resolutions, in previous years, have come forward just about money.”

Maggiano voiced concern about those proposals. He said there was no clear indication where the money would go and some in the diocese had “no clear sense of what it meant.”

“We had a lot of people who didn’t understand the history; that didn’t know why we were talking about this, and if it had passed, it would have been a one-time thing that we would have patted ourselves on the back for,” he said. “It would not have had a huge impact on our diocese, nor transforming the culture and behavior of our diocese, and would not likely have much of an impact on wherever the money would have ended up going.”

“We are way past the time of indulgences,” he said. “The church can’t buy [its way out] of its previous sin. And no matter how big of a check we cut, it doesn’t undo the sins of the past.”

There are multiple approaches to reparations. Symbolic reparations, where a memorial or something similar is erected, is one of them. For example, the diocese has placed grave markers to identify enslaved Black people in parish cemeteries.

“[Symbolic reparations] are a permanent way to recognize the past injustices and make the history of slave holding by a church or university less likely to be forgotten again,” Oast explained.

However, Oast said, there are other was of to do repair. She said religious institutions can also create scholarships for Black people, as well as provide financial assistance to Black churches that are outside the denomination.

“Each case is going to need to be individual, depending on the resources of the church and the needs and wishes of the local Black community,” said Oast. “In every case of reparations, the institutions should first meet with leaders of the Black community and have a dialogue about what would be meaningful. These ideas listed here might not be at all what is wanted by a particular community.”

I shared with Brown, former associate professor at Morgan State University, the School of Community Health and Policy, that, in terms of reparations, the diocese may be interested in creating programs for various Black communities as a form of reparations. Brown said certain programs such as scholarships and others are helpful, but will only help Black individuals within the community and not the whole community. For example, Brown said, speaking specifically of Baltimore, scholarship programs will not undo what he calls Baltimore apartheid (segregation and the mining of resources by powerful institutions).

“In the social sciences, we talk about the unit of analysis, and people think when they are doing something for [individuals] they are doing something for the entire community,” he explained. “Individuals and communities are two different units of analysis, two different entities. If you inflict harm upon entire communities, then only establishing programs to help certain people will be insufficient to redress and repair the damage that these white churches help the cause in Baltimore city.”

A solution that would benefit the entire community, Brown said, is for white churches to help to fix lead poisoning in Baltimore. In redlined Black communities, slumlords, with the assistance of local government, neglected their responsibilities to those properties, which in the process exposed tenants to lead paint. Though lead paint cases have declined in Baltimore, the problem still exists.

“This is one concrete form of damage that racial segregation in Baltimore helped to cause and is still causing,” said Brown. “There is an obligation for white churches in Baltimore to do everything in their power to undue Baltimore apartheid.”

Recently, in an interview with Religion News Service, Sutton said the “diocese is moving methodically after years of conversation about reparations to figuring out how that will be lived out financially and otherwise.”

“We don’t have all the solutions, we don’t know everything that’s going to fix the problem, and so we’re going to be humble in even what we think we can accomplish. But, by God, we’re going to do something,” said Sutton.

Delonte Harrod can be reached theintersectionmagazine@protonmail.com.