Some “Essential” Jobs Are Still In The Queue to be Automated

The pandemic may speed up job replacement.

Sign Up For The Newsletter

〰️

Sign Up For The Newsletter 〰️

Before Covid-19 swept through America, low-wage workers and activists were battling in the states to raise the minimum wage, often referred to as the Fight for $15. Consequently, some states have raised the minimum wage. Maryland’s minimum wage will increase over time, eventually reaching $15 by 2025. However, these same low-wage employees, at some point, were deemed “essential” during the pandemic, illuminating the reality that they’re the ones keeping the economy, and our lives, afloat. For a while, essential employees were given hazard pay, which temporarily increased their pay. Months into the pandemic, companies cut essential employees’ hazard pay.

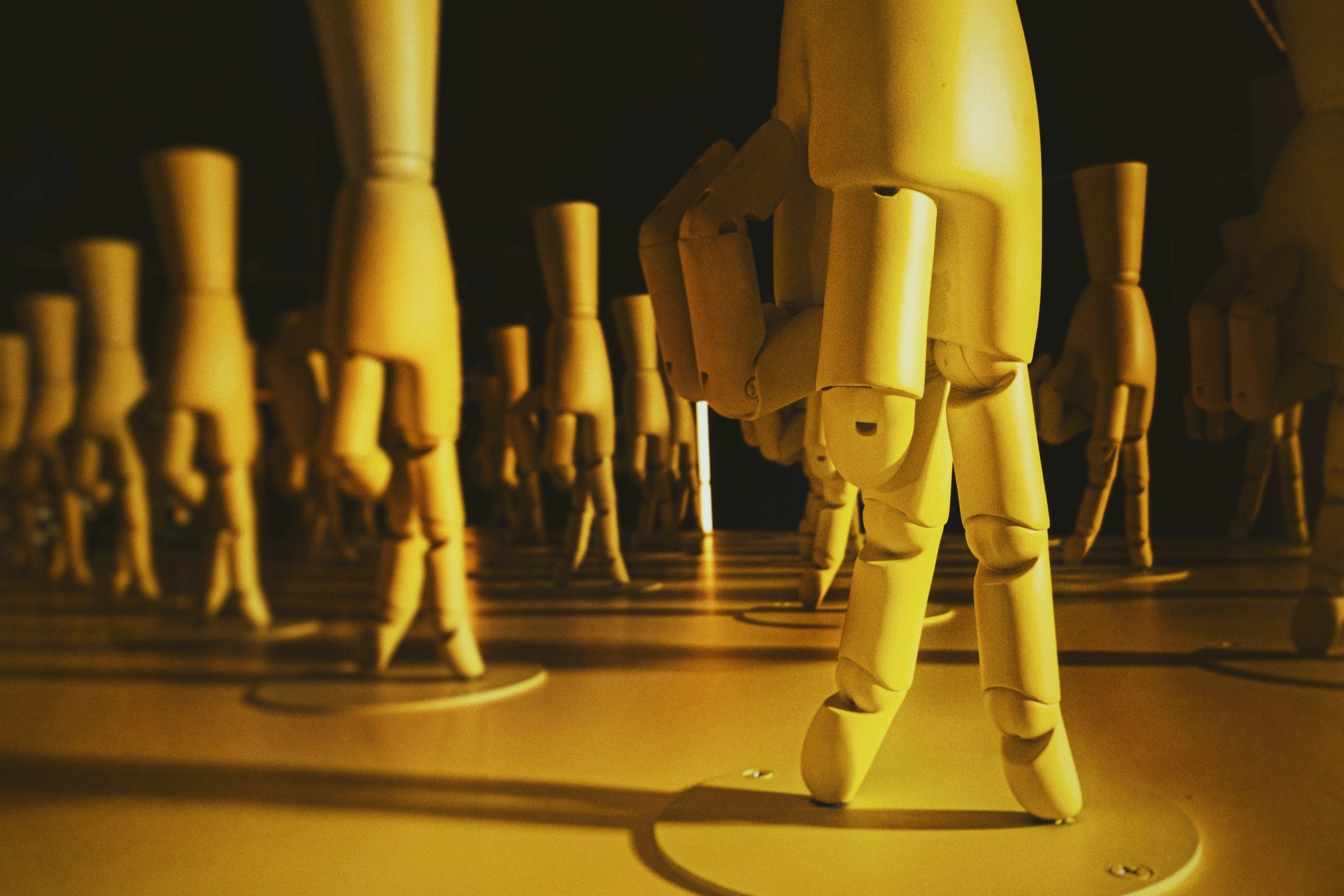

Photo by Jason Yuen on Unsplash

The problems continue to mount for low-wage essential workers. Companies have cut ties with thousands of low-wage essential workers due to COVID-19. Yet, there still is an underlying reality at play, one that existed before COVID-19. Some low-wage jobs, already ripe with employment insecurity, are still in the queue to be automated, and COVID-19 could speed up the process.

In 2019, a Brookings Institution’s study showed that foodservice jobs — cooks and food fast workers, for example — have a 70 to 100 percent chance of automation. Such job replacements (or, what some economists refer to as, employment transformation) disproportionately affect African American and Latino communities.

The talk of automation negatively impacting Black and Latinos communities has been well documented over several years. Back in 2018, the Intersection Magazine, along with Black media outlets, wrote about it.

“Even before COVID-19, Amazon, as well as other retailers, has been on a mission to transform labor.”

The Normalcy of Robots

Americans have been living with automation for a while. For example, fast food, retail, and grocery stores have implemented self-checkout robots. Daron Acemoglu, professor of economics at MIT, who referred to self-checkout tech as “so-so technologies,” said this kind of tech has a worsened customer shopping experience.

“So-so technologies are cost-saving devices for firms that just reduce their costs a little but don’t increase productivity by much. They create the usual displacement effect but don’t benefit other workers that much, and firms have no reason to hire more workers or pay other workers more,” he said in an interview with World Economic Forum, an international non-profit organization.

Even before COVID-19, Amazon, as well as other retailers, has been on a mission to transform labor. Amazon has opened approximately 26 Amazon Go cashier-less convenience stores around the nation. The company has also opened its first cashier-less grocery store in Seattle, Washington, and it plans to open more stores in various gentrified cities throughout America (Chicago, San Francisco, Washington D.C., and Philadelphia). Amazon is trying to sell its technology to other retailers, including Target. Prince George’s County has about 8 Target stores that exist in wealthy (as well as the mixed-income) neighborhoods near the nation’s capital. During the pandemic, Walmart — which, according to the latest data has 1.4 million employees (21 percent African American, 15 percent Latinos, 5 percent Asian American and Pacific Islanders and 1 percent Native and Alaskan Indian) — opened its first cashier-less store in upstate New York. Additionally, some Walmarts use robots to clean floors, stock shelves, scan products, and unload and sort packages on trucks. At best, these robots work alongside employers. The retail chain 7-eleven is also interested in cashier-less technology. These are stores that often exist in lower-income neighborhoods as well as others. David Autor, co-chair at MIT Task Force on the Work of the Future, and Elisabeth Reynolds, executive director of MIT Task Force on the Work of the Future, wrote in an essay that Boston warehouses used robots to disinfect them, and due to the coronavirus, meatpacking plants could accelerate the adoption of robotic automation. The coronavirus has rapidly spread within meatpacking plants, causing workers to quarantine at home. A host of other retail and grocery stores are also looking to implement automation, which also impacts rural America.

“Americans have lost over 8,011,181 low wage jobs, according to the Urban Institute.

During the spread of the pandemic, Americans have lost 8,011,181 low-wage jobs, according to the Urban Institute. Nationally, the food and accommodation industry has suffered the most with 2,846,224 unemployed. The health care and social assistance industry follows with 868,542 unemployed, followed by retail with 615,369 unemployed.

Back in May, before leaving his position, Andrew Schaufele, former director of the Bureau of Revenue Estimates, prophesied that due to the pandemic low-wage employees in Maryland would be the most impacted. He was right. Low-wage workers in Prince George’s County, Maryland — a mostly African-American middle-class county with pockets of poverty — have lost thousands of jobs. (The county leads the state of Maryland in confirmed coronavirus cases). Businesses in Prince George’s County have fired, or let go, 29,142 low-income employees. Of that, 11,115 are within the food and accommodation services, 3,626 health care and social assistance employees, and 2,819 are retail employers, which serve as the top-three jobs eliminated, according to the latest data. In addition to all of this, women This is compounded by low workers, Schaufele said, that never returned to the job market during the first recession. Prince George’s County’s unemployment rate is 9.9 percent, down from 10.9, which is higher than the state average (8.3 percent).

Schaufele said that the recovery for low-wage workers will be slow — and that the state has an opportunity to reinvest in retraining opportunities.

Due to the lackluster implementation of laws to mitigate the spread of the virus, it has begun to spread again. States are reverting to earlier restrictions to prohibit the spread of the virus. Such restrictions slow down hiring and rehiring of low-wage workers.

The Paycheck Protection Program funds did stop some companies from closing and to continue to pay employees for a while. However, employers still fired their employees. Back in June, CNBC reported that a National Federation of Independent Business study found that 14 percent of businesses would fire their employees after using up Paycheck Protection Program funds. However, the latest numbers show that it has turned out to be 22 percent. Low-wage workers may linger in the unemployment wilderness, which may eventually add to poverty in certain states. A second coronavirus stimulus package may be on the verge of passing. Recently, the president has signed executive orders pushing out parts of the relief for Americans. However, as predicted the president slashed the extra unemployment insurance benefit from $600 to $400. To make matters worse, not all will who apply for unemployment receive the extra benefits. Such a seemingly minor drift from $600 to $400 will affect will disproportionately affect African Americans and Latinos.

But it’s not only the lack of unemployment funds, nor the lack of funds to pay low-wage employees, it’s also telework — among high skilled/ white-collar jobs — that is furthering job insecurity.

“If [telework] displaces a meaningful fraction of professional office time and business travel, the accompanying reductions in office occupancy, daily commuting trips, and business excursions will mean steep declines in demand for building cleaning, security, and maintenance service; hotel workers and restaurant staff; taxi and ride-hailing drivers; and myriad other workers who feed, transport, clothe, entertain, and shelter people when they are not in their own homes,” Autors and Reynolds wrote.

They add: “A substantial, long-run demand contraction in these services will mean significant job loss — or lock-in of existing COVID-induced job losses — and a sustained period of labor market adjustment.”

(Low-wage jobs’ insecurity is further compounded with uncertainty when companies increase the minimum wage because it is likely that those positions will soon be automated ).

However, telework — according to Autor and Reynolds — has an economic upside for the companies that pay a lot of money for employers’ travels and meals. It reduces company expenses for employers and employees.

“Not only is providing and maintaining physical offices costly for employers, but also the need to be physically present in offices imposes substantial indirect costs on the employee,” Autor and Reynolds wrote.

There is another phenomena. White-collar jobs are being replaced by artificial intelligence, not automation. This has created openings within, what is known as, high-wage jobs. Though these openings in high-wage jobs are present, it doesn’t necessarily mean that low-skilled workers have or will have the opportunity to fill the void. Low-wages workers — unless they have received specialized training courses and or completed a digital literacy program- lack the varied skills to work as a data analyst, in upper management, visual data design, etc. Employers often fill these high skilled job vacancies with current employees with similar skills, do in-house training for a new position, or hire temporary contractors, which often saves them money.

“Digital literacy and problem-solving skills are fundamental to weathering current and future technological disruptions.” — Molly Bashay, now a senior policy analyst at the Center For Law and Social Policy.

Policy and Digital Literacy

Photo by

on

Improving workers’ skills, aka upskilling, for this not-so-new world of work is widely talked about as a solution. But it’s not only that workers need to improve digital skills, but they also, according to Molly Bashay, former National Skills Coalition policy analyst, need to become digitally literate. For example, many workers may know how to use Google (digital skill) to check an email, search, and have basic knowledge about spreadsheets, etc. However, there is a difference in knowing how to use Google and knowing how to use its many applications (data collection and visualization tools) to fulfill a job requirement.

The National Skills Coalition recently released a study — written by Molly Bashay that recommends policy solutions that will ensure that everyone has access to digital learning skills. Bashay estimates that 48 million people lack digital literacy. Bashay advocates for, among other things: a federal commitment to occupational digital literacy; create a new national grant program, or Digital Literacy Upskilling Grants,” which could expand access to beneficial digital literacy programs, and for the federal government to “develop a measurable national standard for industry-specific digital upskilling efforts.”

“Digital literacy and problem-solving skills are fundamental to weathering current and future technological disruptions,” wrote Bashay, now a senior policy analyst at the Center For Law and Social Policy. “…. Workers also need full access to digital devices and reliable home broadband connections to be fully effective in a digitalizing economy. Even before the pandemic, the nature of work was already transforming to depend on new digital systems, processes, and skills. For many industries — especially those with more highly automatable roles or more easily digitized functions — digital skills are a vital threshold competency for the new hires and incumbent workers businesses depend on. Without these skills, workers are being left behind.”

If implemented, such policies would give local organizations the funds they need to reach their communities to provide low-cost and even free classes. These classes would reach what I deem as the in-between people; community members who may have lost their jobs during COVID-19, and those who do not have the money nor the time to attend full-time college courses. However, they may have the time to attend a free self-paced digital literacy class.

Other solutions, The Intersection reported, could come from HBCUs. Andre Perry, author, Brooking Institution Fellow, and education columnist, once wrote that HBCUs should partner their college campuses as tech startup labs.

As far back as 2016, Google committed to working with HBCUs, and Hispanic or Latino serving institutions to create a tech pipeline. The company created the Tech Exchange, an exchange program that teaches tech courses at its Google campus.Apple has partnered with HBCUs, mainly in Southern states, to teach students coding. Tesla just announced its partnership with Houston-Tillotson, an HBCU in Austin Texas, a gentrified city that is now a booming tech hub, to hire students as interns, and apprentices at the company.

“The employment opportunities created by Tesla will provide a direct career path with access to a full array of benefits that align with HT’s Career Pathways Initiative, which is focused on preparing students for mid-to-high-skilled careers in a dynamic and innovative global environment,” HT said in the welcome letter, according to CleanTechnica.com.

To solve this growing unemployment problem, and skills gap, there will need to be collaboration among local Black institutions, and local and federal policy that curves the negative effects of economic effects on the African American, and Latino communities. As for now, as COVID-19 continues to surge, and as technologists and some companies invest in robots, jobs are disappearing, reshaping the way we work and not.

Check out other Tech News

Delonte Harrod is the CEO, editor, and reporter at The Intersection Magazine. If you have story tips or suggestions contact:theintersectionmagazine@protonmail.com

The fight to provide Maryland citizens with a livable wage continues. On Monday, Oct. 7, members from activist organizations stood alongside Tom Dernoga (District 1), and Krystal Oriadha (District 7) at The Wayne K. Curry building in Upper Marlboro to publicly advocate for a bill that would index the minimum wage in Prince George’s County.